Robert Lazu Kmita | Remnant Columnist, Romania

Today’s reality doesn’t allow us any escape: things are as we see them. So the Savior’s statement that the “gates of hell” will not overcome the Church can only mean one thing: just as it happened during His first coming to earth, the faith revealed by the heavenly Father to Peter will remain unbeaten – until the end of the world – in those unknown and disregarded true Christians (disregarded by both Church hierarchs and political leaders).

In the past half-century, almost all the inventions based on the storage and transmission of images have been created and promoted globally. The emergence of the Internet was at the height of this process. Therefore, a true tsunami of images hit all our homes through these digital devices. The consequences of such a global phenomenon are really worrying.

On the evening of Saturday, September 19, 1846, two young shepherds, Mélanie Calvat (14 years old) and Maximin Giraud (11 years old), encountered a wondrous and luminous Lady in tears: the Holy Virgin Mary. Deeply saddened, the Queen of the Universe conveyed a message to them addressed to all. Her unforgettable words mentioned the “strong and heavy” hand of her Son that she could no longer hold back. The cause was the sins of humanity: the violation of the commandment to attend Sunday and holy day Mass, along with blasphemous swearing and neglect of fasting periods. Punishments, especially famine, were imminent. Asking the children how to pray, she recommended at least one Our Father and one Hail Mary when more could not be done.

Since the earliest times of the world before Christ was born, God began to sprinkle prophetic signs in the history of the Jewish people of what was to come. Without exception, the Holy Fathers and Doctors of the Church have revealed the pre-figurations of baptism in the Old Testament, all of which found their fulfillment after the Incarnation of Jesus Christ: the creation of the world – when the Spirit of God hovered over the waters; Noah’s ark which traversed the waters of the flood; the passage of the people of Israel through the Red Sea.

Disturbing news

Whether we look towards our own Church, the Catholic Church, or towards Christian denominations, towards the ecclesiastical hierarchy or towards the secular world, towards ecclesiastical personalities, showbiz superstars, or celebrities from the world of film, in recent decades scandals regarding their sexual sins have grown exponentially. We often hear about such events affecting various communities, whether religious or not. Despite distortions and even exaggerations in the media, unfortunately, many of them are based on real facts.

Without a doubt, in this interpretation lies one of the most profound lessons of the darkness during the crucifixion of the Savior Christ: the “eclipse” of faith. There is no more terrible test, for any of us, than the Cross.

One of the most fiercely debated issues in the entire history of the Christian Church is that of the status of sacred images. Regardless of the details and historical episodes of this dispute, its primary reference is always the third commandment of the Decalogue transmitted to us by God through Moses:

“Thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing, nor the likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, nor of those things that are in the waters under the earth” (Exodus 20:3).

At first glance, this article of the Decalogue seems to prohibit any sacred image. However, the mere presence on the ark of the law of the “two cherubims of beaten gold” (Exodus 25:18), as well as other similar examples from the Old Testament, show us that, in fact, it is not about an absolute prohibition. In this sense, Bishop Richard Challoner (1691–1781), in his commentary on this point, states the following:

“All such images, or likenesses, are forbidden by this commandment, as are made to be adored and served; according to that which immediately follows, thou shalt not adore them, nor serve them. That is, all such as are designed for idols or image-gods, or are worshipped with divine honour. But otherwise images, pictures, or representations, even in the house of God, and in the very sanctuary so far from being forbidden, are expressly authorized by the word of God. (See Ex. 25:15, and etc.; chap. 38:7; Num. 21:8, 9; 1 Chron. or Paralip. 28:18, 19; 2 Chron. or Paralip. 3:10).”

Despite the fact that such clear explanations have always existed in Christian Tradition, the great iconoclastic crisis in the Byzantine world, which unfolded in the 8th and 9th centuries AD, could not be prevented. Although it ended by emphasizing the lawful use of sacred images in churches in the Second Council of Nicaea (787), whose teachings were developed under the influence of great theologians such as the saints John of Damascus (c. 675 or 676–749) and Theodore the Studite (759–826), the debate was reignited by the spread of Protestant heresies. Today, under the strong influence of the liturgical revolution (i.e., protestantization), numerous churches suffer from three major symptoms of this misunderstanding of the Decalogue.

It is absolutely necessary, in a context where we are still accused of idolatry (especially by neo-Protestants), to know the teachings of the Church. Thus, besides deepening our own faith, we may perhaps succeed in combating erroneous (i.e., heretical) opinions.

The first, the most serious, is manifested by the almost complete exclusion of sacred images from post-conciliar Catholic churches. While this phenomenon is less noticeable in countries where older churches are still in use, in places where new churches are built, they are often devoid of religious icons. During my early travels in the United States, in New York, Phoenix, and Cary, I saw for the first time Catholic churches where there were no religious images whatsoever. Without exception, they resembled more conference halls or sports venues and had only a single crucifix above or behind the altar. Occasionally, a few statues of better-known saints like Teresa of Lisieux and Padre Pio could be found. Otherwise, there were no sacred images.

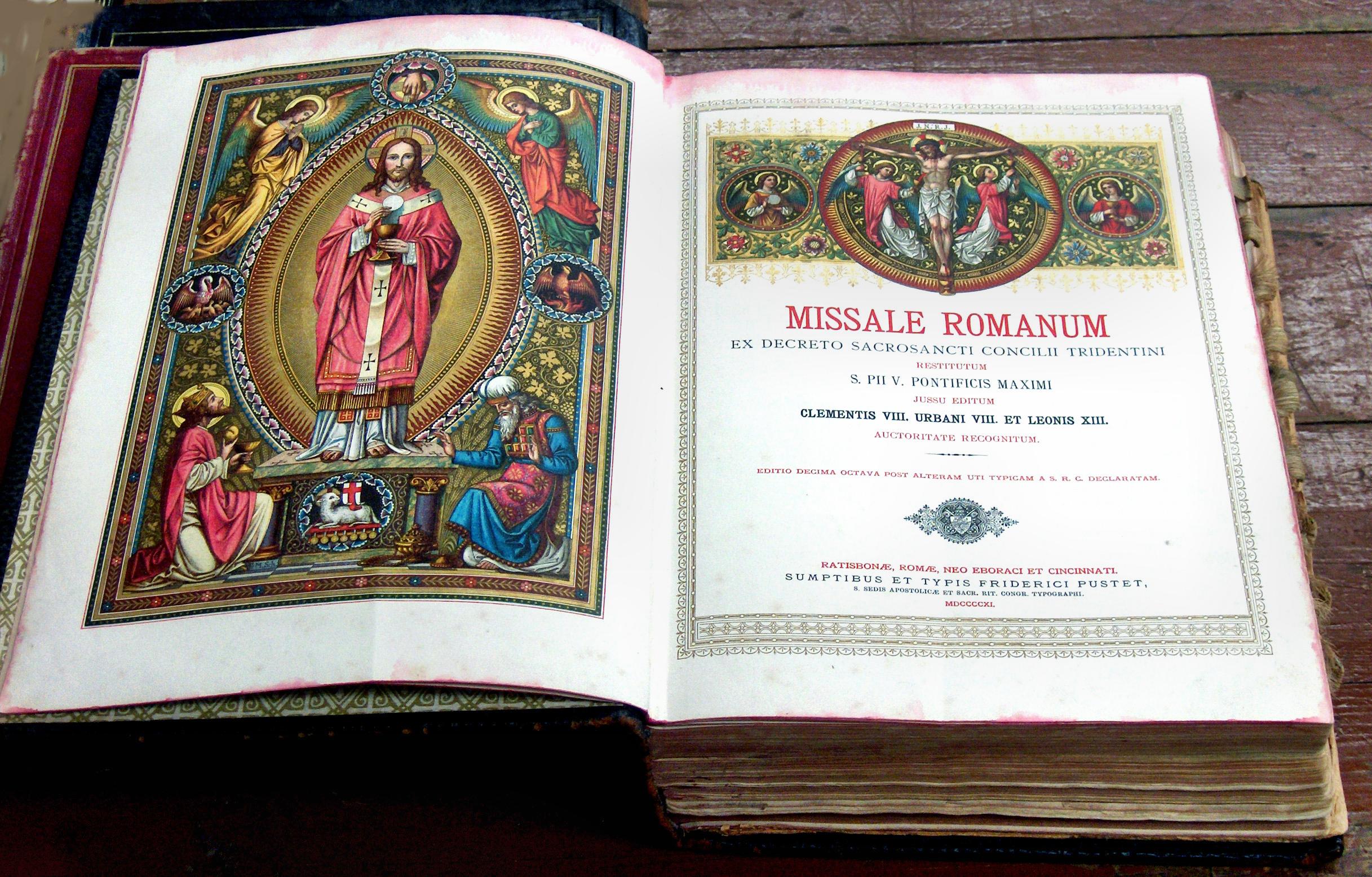

A second symptom, equally widespread though not necessarily as severe, consists of replacing images that adhere to the old canons of sacred aesthetics with naturalistic or even post-modern and abstract religious paintings. Often of questionable quality, these paintings make visible the third symptom, namely, the lack of attention to the true requirements of beauty in religious representations. In short, most paintings of this kind are ugly. Often they border on kitsch, as exemplified by the creations of Marko Ivan Rupnik, for instance. Opposed to all these symptoms, the presence of authentic Christian religious art, truly beautiful, is the defining element of authentic Catholic Tradition. It is enough to look at the images from the 18th edition (1915) of the Roman Missal printed by Friedrich Pustet’s printing house to see what respect for the beauty of holy beings and things means.

Considering all these aspects related to the liturgical revolution triggered by the eclipse of traditional Christian faith, the first thing I will say is that all deviations originate from the confusion between idol (Greek εἴδωλον) and icon (Greek εἰκών). Bishop Challoner’s explanation is precisely based on the difference between the two entities. It is absolutely necessary, in a context where we are still accused of idolatry (especially by neo-Protestants), to know the teachings of the Church. Thus, besides deepening our own faith, we may perhaps succeed in combating erroneous (i.e., heretical) opinions.

In the world of the Old Testament, which suffered the consequences of the original sin of Adam and Eve, the face of God was hidden from humanity. It was only through the Incarnation of the Son of God that this face became visible again. Therefore, the appearance of icons in the early centuries of the Christian era marks the extraordinary difference between the two worlds.

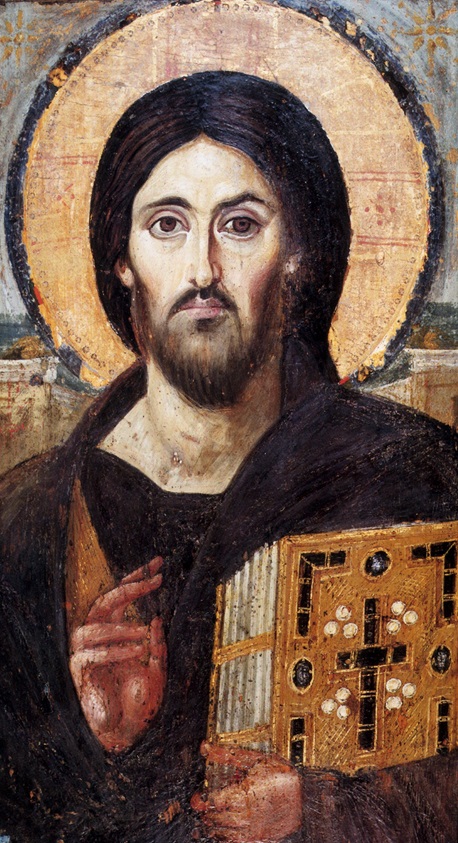

As I have already mentioned, the main argument invoked by those who reject icons comes from the Old Testament. Starting from the third commandment of the Decalogue, it has been assumed that even in the context of Christianity, religious images have no place in religious worship. Behind this attitude lies a grave error. An error that, in fact, implicitly denies the Incarnation of the Divine Logos – the second Person of the Holy Trinity, Savior Jesus Christ – and the extraordinary consequences of this epochal historical event. This is why the iconic representation par excellence is not that of the Virgin Mary, nor are those of the saints and angels of God. The central representation (i.e., icon) of the entire Christian iconographic program is that of our Savior Jesus Christ. Of course, all other sacred images that represent Him as God-man are equally legitimate, but the latter occupies an exceptional role due to the fact that the second person of the Holy Trinity became man by assuming in His person, alongside the divine nature, the human nature.

In the world of the Old Testament, which suffered the consequences of the original sin of Adam and Eve, the face of God was hidden from humanity. It was only through the Incarnation of the Son of God that this face became visible again. Therefore, the appearance of icons in the early centuries of the Christian era marks the extraordinary difference between the two worlds: the old one, before Christ, which did not have access to the Kingdom (the gates being guarded by cherubim with a flaming sword), and the new one, for which the Kingdom is once again accessible and God has become visible through His Incarnation from the Virgin Mary.

Considering this essential point, the Church has defended sacred images from ancient times. What it has actually defended is the realism of God’s Incarnation, the fact that this absolutely extraordinary event is not a fiction but a crucial historical truth. One of the most important teachings was expressed within the Second Council of Nicaea (787):

“As the sacred and life-giving cross is everywhere set up as a symbol, so also should the images of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the holy angels, as well as those of the saints and other pious and holy men be embodied in the manufacture of sacred vessels, tapestries, vestments, etc., and exhibited on the walls of churches, in the homes, and in all conspicuous places, by the roadside and everywhere, to be revered by all who might see them. For the more they are contemplated, the more they move to fervent memory of their prototypes. Therefore, it is proper to accord to them a fervent and reverent veneration, not, however, the veritable adoration which, according to our faith, belongs to the Divine Being alone – for the honor accorded to the image passes over to its prototype, and whoever venerate the image venerate in it the reality of what is there represented.”

When a mother kisses the photograph of her son who has gone to war, she does not “venerate” the material from which the photograph is made. This is exactly the sense in which the faithful kiss and honor icons: they mark through these gestures a profound communion with the divine persons represented.

So sacred images can and should be venerated. But we must understand exactly the nature of the gestures of venerating icons (adoration is reserved exclusively for God). We do not venerate the material from which the icon is made (wood, ceramic, canvas, etc.), just as we do not venerate the paints with which it is painted. In fact, we honor the persons from the unseen world who are represented, by similarity, in icons. This is the true meaning of veneration. In a well-known example, it is emphasized that when a mother kisses the photograph of her son who has gone to war, she does not “venerate” the material from which the photograph is made. What normal person would do such a thing? The kiss is, in fact, a gesture of communion with the person represented in that photograph. This is exactly the sense in which the faithful kiss and honor icons: they mark through these gestures a profound communion with the divine persons – the “prototypes,” as the Second Council of Nicaea says – represented.

Finally, there is another aspect regarding the importance of images: they educate us. They teach us the truths of faith. In a world flooded with profane images, we need sacred images more than ever. Unlike the profane and often profane images of today’s media culture, icons are true windows to the heavenly Jerusalem, where in the bosom of the Triune God – the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit – dwell all the angels and saints, upon whom shines the beauty of she who “has been raised above the cherubims, and has become higher than the seraphims” – the Holy Virgin Mary.

One of the great defenders and teachers of the iconoclastic cult, Saint John of Damascus, expressed with very beautiful words this reality of nurturing and growing the soul through sacred icons:

“The beauty of the images moves me to contemplation, as a meadow delights the eyes and subtly infuses the soul with the glory of God.”

Latest from RTV — CHRIST is KING: Candace Owens Is Right

Thus, some of the most beloved creatures, which do so much good to humans through all their products (honey, wax, propolis, pollen, etc.), have been introduced into the prayers of the Church, becoming symbols through which we are taught both the mysteries of faith and how we must live as true Christians, working diligently and devotedly for the mystical body of our Savior Christ, under the guidance of His mother. Actually we are the “bees” invited to bear fruit: “the one thirty, another sixty, and another a hundred” (Mark 4:20).

The absolute axiom of interpreting the four Gospels, which has always been followed by the Holy Fathers and Doctors of the Church, is that nothing of all that the Savior Christ did on this earth was devoid of meaning, nor was it done at random.

The main reference point of our lives, therefore, is the Cross. It is what helps us traverse the tumultuous ocean of the “world” like a lifeboat. It is what protects us from the fire of passions and vices through its fireproof qualities, similar to cork wood. At the same time, with the image of the monk tied to the mast floating at the mercy of the waves before our eyes, we understand that without it, we would sink immediately.